Why Go is a good fit for agents

Since you’re here, you might be interested in checking out Hatchet — the platform for running background tasks, data pipelines and AI agents at scale.

Alexander Belanger

Published on June 3, 2025

Like seemingly everyone else on the planet, we’ve been spending the last few months fussing over agents.

In particular, we’ve been seeing the adoption of agents drive the growth of our orchestration platform, so we have some insight into what sorts of stacks and frameworks — or lack thereof — work well here.

One of the more interesting things we’ve seen is a proliferation of hybrid stacks: a typical Next.js or FastAPI backend, coupled with an agent written in Go, even at a very early stage.

As a long-time Go developer, this is rather exciting; here’s why I think this will be a more common approach moving forward.

What’s an agent?

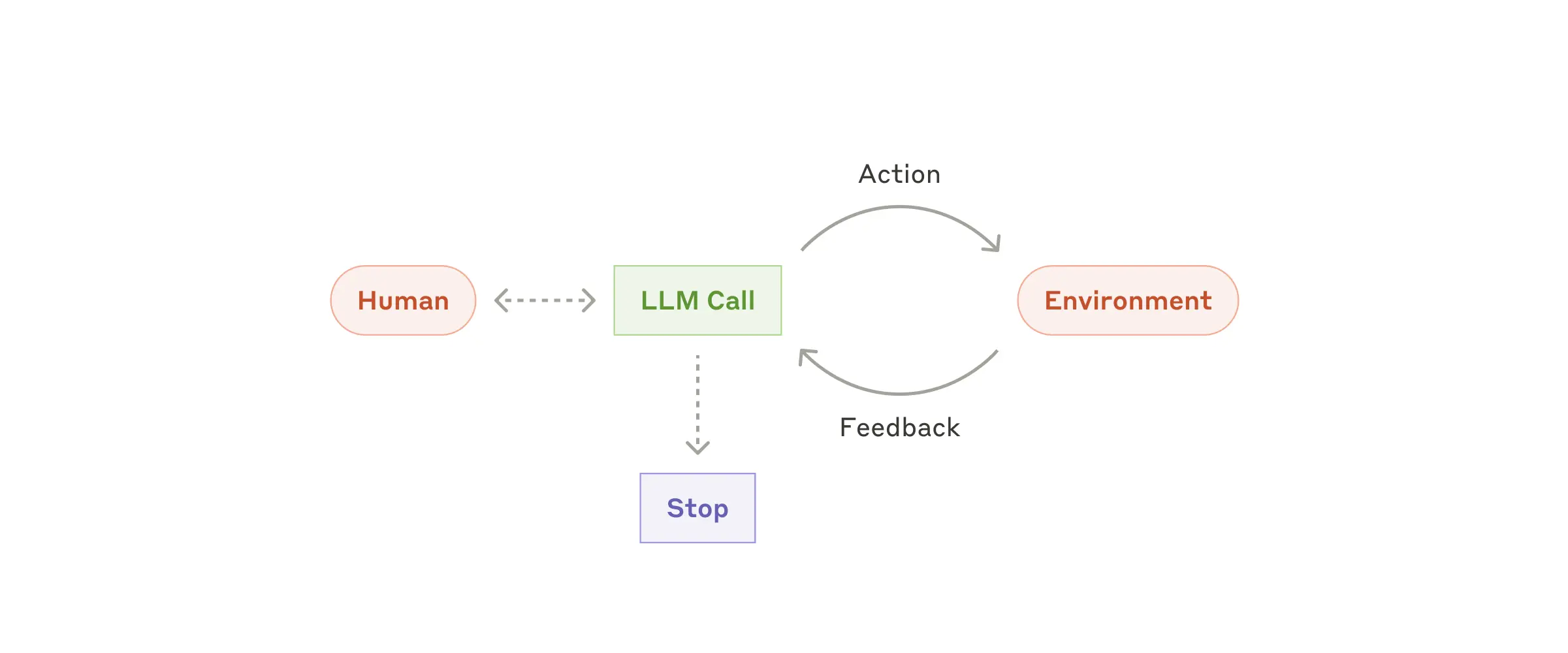

Terminology here is muddled, but in general I’m referring to a process which is executing in a loop, where the process has some agency over the next step in its execution path. Contrast this with a predefined execution path, like a set of steps defined as a directed acyclic graph, which we’d call a workflow. Agents often contain an exit condition based on maximum depth or a condition (like “tests pass”) being met.

Source: https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/building-effective-agents

Agents typically have a number of shared characteristics when they start to scale (read: have actual users):

- They are long-running — anywhere from seconds to minutes to hours.

- Each execution is expensive — not just the LLM calls, but the nature of the agent is to replace something that would typically require a human operator. Development environments, browser infrastructure, large document processing — these all cost $$$.

- They often involve input from a user (or another agent!) at some point in their execution cycle.

- They spend a lot of time awaiting i/o or a human.

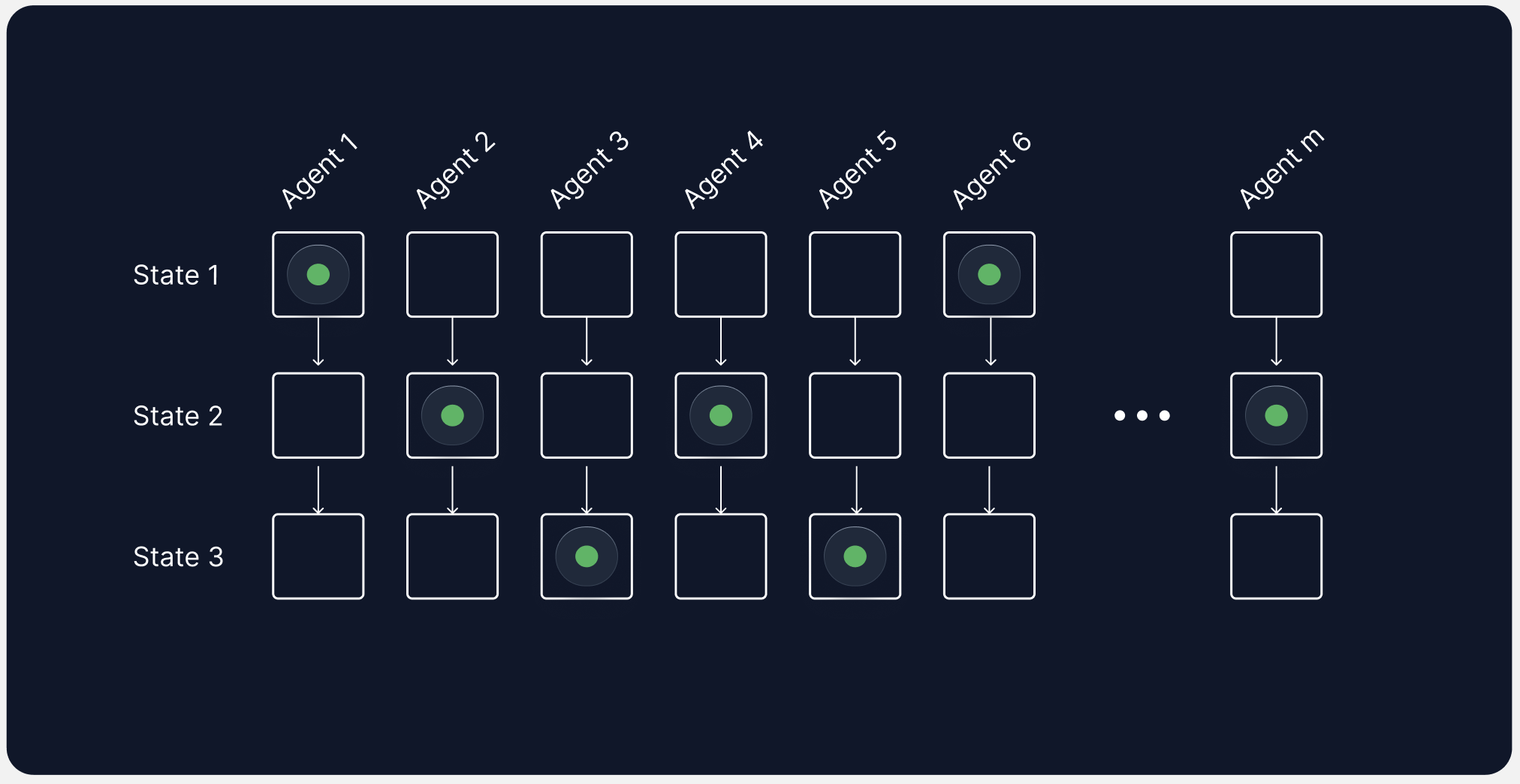

Let’s translate this set of characteristics into runtime. To constrain the problem, let’s assume that we’re dealing with an agent that is executed remotely and not on a user’s machine (though Go would be a great choice for distributing a local agent as well). In the case of remote execution, it would be incredibly expensive to run a separate container for each agent execution, so in most cases (particularly when our agent is simple i/o and LLM calls), we are going to end up with a bunch of lightweight processes that are running concurrently. Each process can be in a given state (for example, “Searching files,” “Generating code,” “Test”). Note that the ordering of states is not the same in for different agent executions.

This system of many concurrent, long-running processes is quite different from a traditional web architecture of ~10 years ago, where requests to a server were much faster, and thousands of daily users could be served efficiently using some caches, efficient handlers and OLTP databases.

It turns out, this shift in architecture is really well-suited to Go’s concurrency model, reliance on channels for communication, centralized cancellation mechanism, and tooling built around i/o.

High concurrency

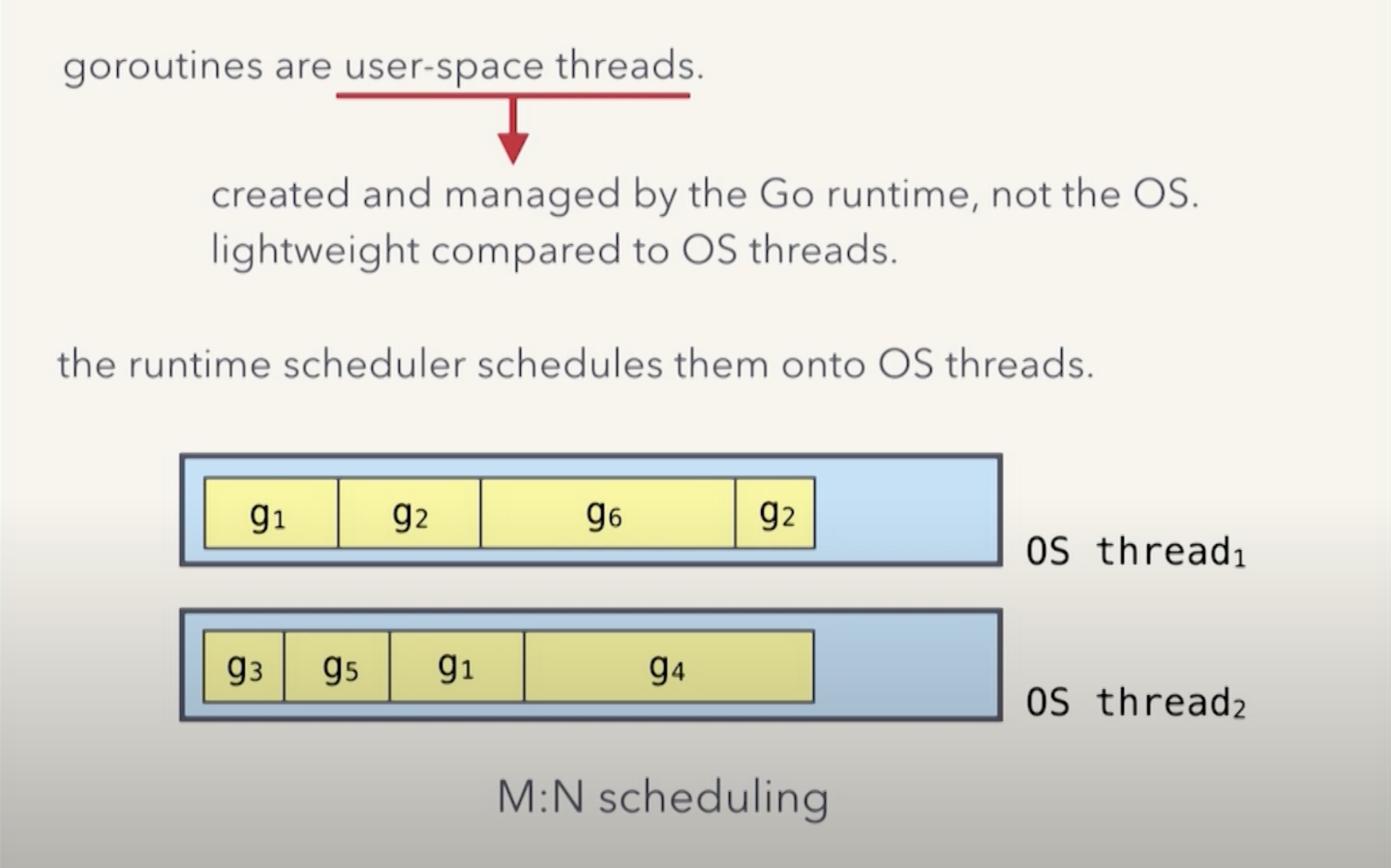

Let’s start with the obvious — Go has an incredibly simple and powerful concurrency model. Spawning a new goroutine costs very little memory and time, as there’s only 2kb of pre-allocated memory per goroutine.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBZlN0izeiY&t=586s

Effectively this means that you can run many goroutines at once with little overhead, and they run on multiple OS threads under the hood which take advantage of all CPU cores in your server. This is rather important, because if you happen to do something very CPU-intensive in a goroutine (like deserializing a large JSON payload), you will see less of an impact than if you were using a single-threaded runtime like Node.js (where you’d need to spawn out to a worker thread or child process for something that blocks the thread) or Python’s async/await.

What does this mean for agents? Because agents are longer-running than a typical web request, concurrency becomes a much greater point of concern. In Go, you’re much less likely to be constrained by spawning a goroutine per agent than if you ran a thread per agent in Python or an async function per agent in Node.js. Couple this with a lower baseline memory footprint and compilation into a single binary, and it becomes incredibly easy to run thousands of concurrent agent executions at the same time on lightweight infrastructure.

Share memory by communicating

For those unaware, there’s a common Go idiom that says: Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.

In practice, this means that instead of attempting to synchronize the contents of memory across many concurrent processes (a common problem when using something like Python’s multithreading libraries), each process can acquire ownership over an object by acquiring and releasing it over a channel. The effect is that each process is only concerned about the local state of an object while it has ownership over that object, but otherwise doesn’t need to coordinate ownership — no mutexes necessary!

To be quite honest — in most Go programs I’ve written, I’ve often used wait groups and mutexes more often than channels, because it’s often simpler (which is in line with the Go community’s recommendations) and there’s only one location where data gets accessed concurrently.

But this paradigm is useful when modeling agents, because an agent often needs to asynchronously respond to messages from a user or another agent, and it’s helpful to think about an instance of your application as a pool of agents.

To make this more concrete, let’s write some example code to represent the core of an agentic loop:

// NOTE: in a real-world example, we'd want a mechanism to gracefully

// shut down the loop and protect against channel

// closure; this is a simplified example.

func Agent(in <-chan Message, out chan<- Output, status chan<- State) {

internal := make(chan Message, 10)

for {

select {

case msg := <-internal:

processMessage(msg, internal, out, status)

case msg := <-in:

processMessage(msg, internal, out, status)

}

}

}

func processMessage(msg Message, internal chan<- Message, out chan<- Output, status chan<- State) {

result := execute(msg)

status <- State{msg.sessionId, result.status}

if next := result.next(); next != nil {

internal <- next

}

out <- result

}(Note that the <-chan means that the receiver can only read from the channel, while the chan<- means that the receiver can only write to the channel.)

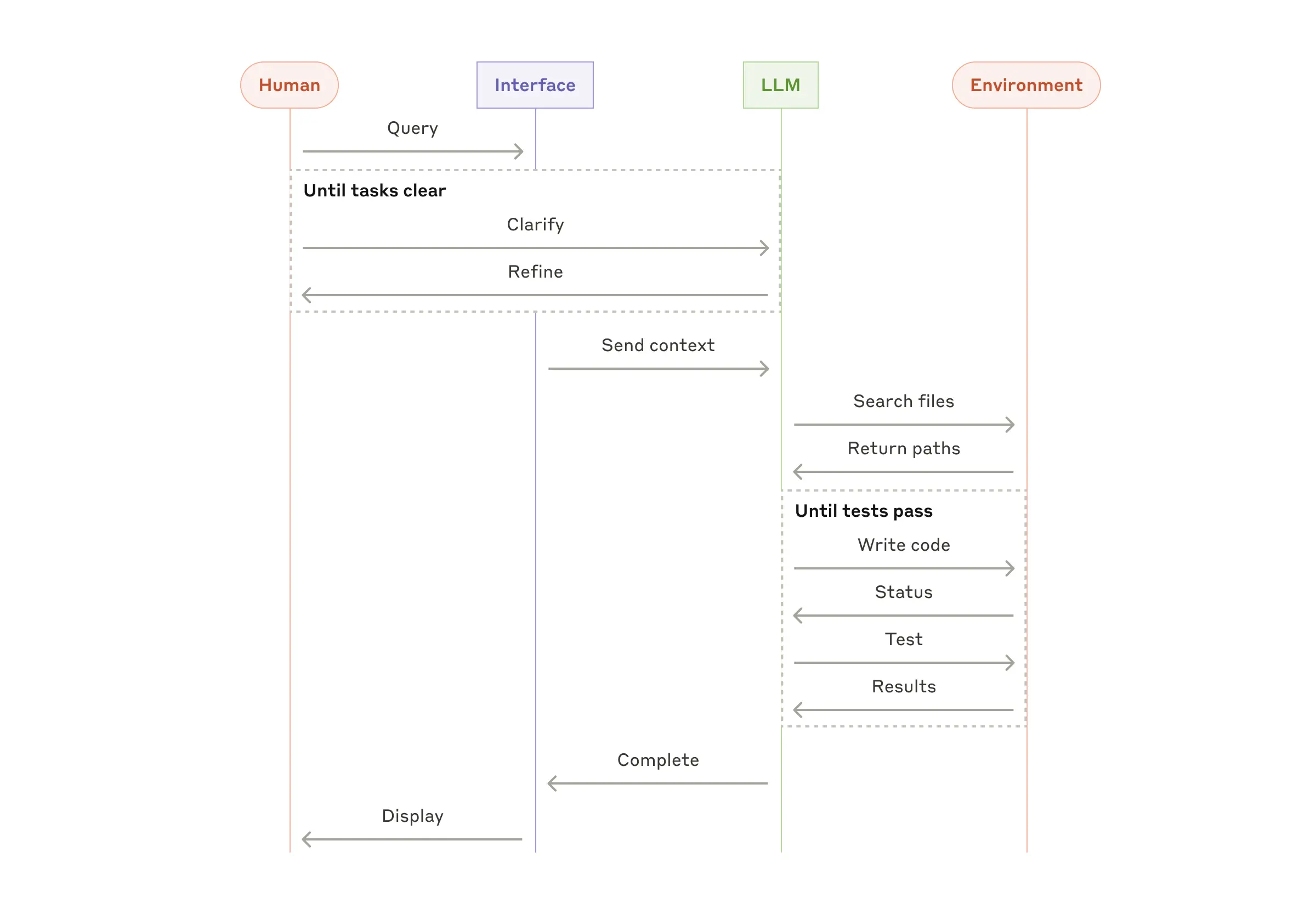

This agent is a long-running process which waits for messages to arrive on the in channel, processes the message, and then asynchronously sends the result to the out channel. The status channel is used to send updates about the agent’s state, which can be useful for monitoring or sending incremental results to a user, while the internal channel is used to handle internal agent loops. For example, the internal loop could implement the “Until tests pass” loop in the diagram below:

Source: https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/building-effective-agents

Even though we’re running the agent as a for loop, the instance of the agent doesn’t have any internal state that it needs to maintain between messages. It’s effectively a stateless reducer, which doesn’t depend on some internal state to make a decision about the next step in its execution path. Importantly, this means that any instance of the agent is able to process the next message. This also allows for the agent to use a durable boundary in between messages, for example writing messages to a database or message queue.

This is a toy example — for a more concrete walkthrough of this Go idiom, much of this is inspired by this codewalk.

Centralized cancellation mechanism with context.Context

Remember how agents are expensive? Let’s say a user triggers a $10 execution, and suddenly changes their mind and hits “stop generating” — to save yourself some money, you’d like to cancel the execution.

It turns out, cancelling long-running work in Node.js and Python is incredibly difficult for multiple reasons:

- Libraries can’t agree on a shared mechanism to actually cancel work — while both languages have support for abort signals and controllers, it doesn’t guarantee that your third-party library calls will respect those signals.

- If that fails, forcefully terminating threads is a miserable process and can cause thread leakage or corrupted resources.

Luckily, Go’s adoption of context.Context makes it trivial to cancel work, because the vast majority of libraries expect and respect this pattern. And even if they don’t: because there’s only one concurrency model in Go, there’s a bunch of tooling like goleak which makes it much easier to catch leaking goroutines and problematic libraries.

Expansive standard library

When you start working in Go, you’ll immediately notice that the Go standard library is expansive and very high quality. Many parts of it are also built for web i/o — like net/http, encoding/json , and crypto/tls — which are useful for the core logic of your agent.

There’s also an implicit assumption that all i/o is blocking within a goroutine — again, because there’s only one way to run work concurrently — which encourages the core of your business logic to be written as straight-line programs. You don’t need to worry about deferring execution to the scheduler with an await wrapping each function call.

Contrast this with Python: library developers need to think about asyncio, multithreading, multiprocessing, eventlet, gevent, and some other patterns, and it’s nearly impossible to support all concurrency models equally. As a result, if you’re writing your agent in Python, you’ll need to research each library’s support for your concurrency model, and potentially adopt multiple patterns if your third-party libraries don’t support exactly what you’d like.

(The story is much better in Node.js, though the addition of other runtimes like Bun and Deno has added some layers of incompatibility.)

Profiling

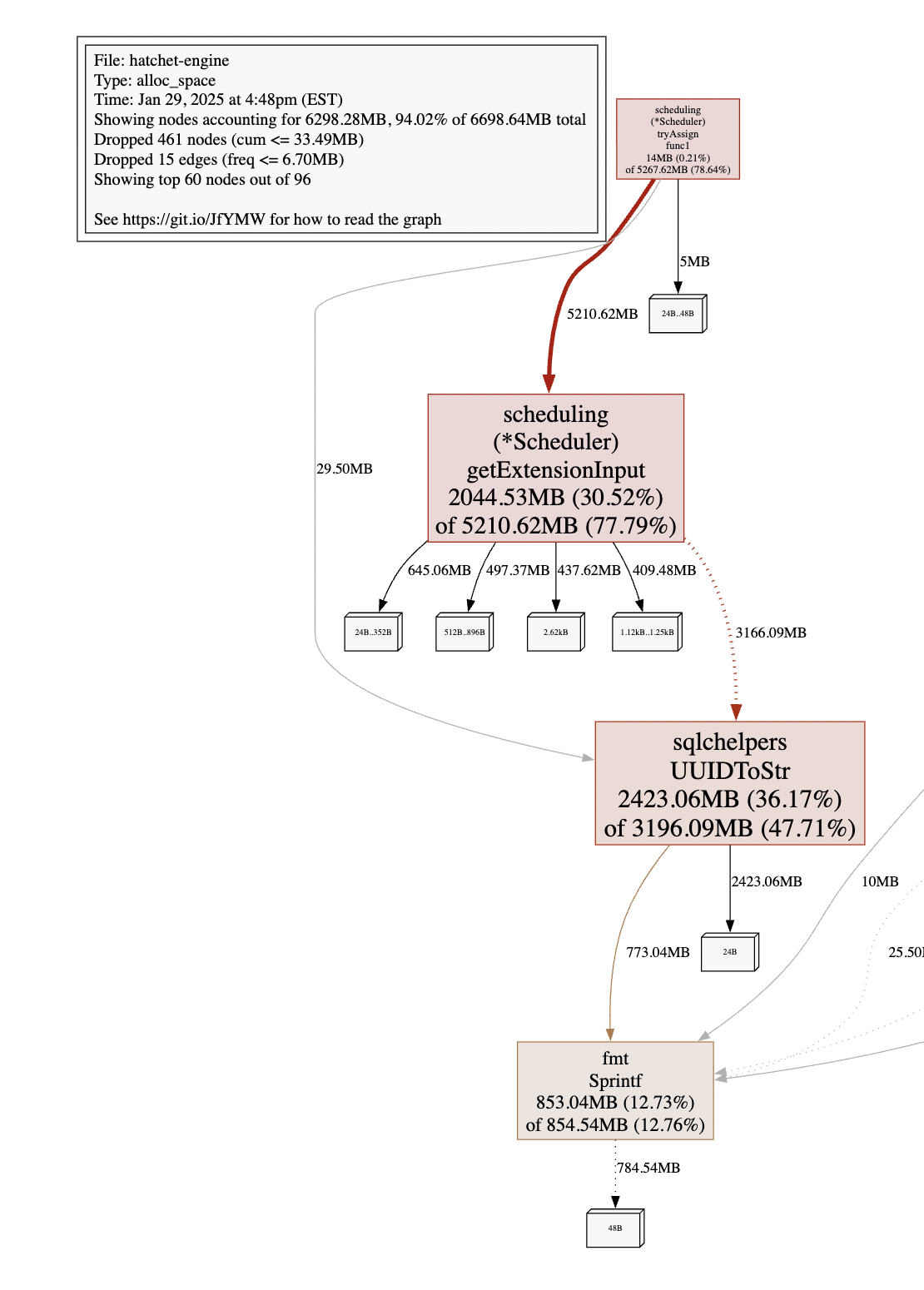

Agents seem to be quite susceptible to memory leaks because of their statefulness and thread leaks because of the number of long-running processes. Go has great tooling in runtime/pprof for figuring out the source of a memory leak using the heap and alloc profiles, or the source of a goroutine leak using the goroutine profiles.

Source: One of my more embarrasing memory leaks

Bonus: LLMs are good at writing Go code

Because Go has a very simple syntax (a common criticism being that Go is “wordy”) and has an expansive standard library, LLMs are quite good at writing idiomatic Go code. I’ve found that they’re particularly good at writing table tests, which are a common pattern in Go codebases.

Go engineers also tend to be anti-framework, which means that LLMs don’t need to track which framework (or version of a framework) you’re using.

The bad parts

Given all of these benefits, there are still a lot of reasons not to use Go for your agent:

- Third-party support still lags behind Python and Typescript

- Using Go for anything that involves real machine learning is nearly impossible

- If you’re looking for the best performance possible, there are better languages like Rust and C++

- You’re a maverick and don’t like to handle errors (you’re not alone)

Subscribe for more technical deep dives

Stay updated with our latest work. We share insights about distributed systems, workflow engines, and developer tools.